When the Normal is Experienced as Something Special

(Guest Post by Angus Forbes)

"Where are you from?" is one of the first questions we are asked when we introduce ourselves. Our home place is a strong identity factor and it bonds us with others who are also connected with it in some way. Most likely, our home place has also influenced the way we are. There is one thing that absolutely everyone living in a place has in common with each other... and that is the place itself. This is cause enough to celebrate both place and each other! (How we define a ‘place’ is another question.) Through denying us access to more exotic places, the Covid19 lockdown has challenged us all to find more value in our immediate locality.

Becoming and staying aware of what makes our home-place different or special is not so easy, but it can start a virtuous circle which benefits both its human and non-human components. We humans enjoy a positive identity reinforcement and in return we may choose to take more care of its source. Parents and kids at my son’s forest kindergarten, for instance, comb the surrounding woods twice a year for litter. This kind of care is not always the case. Oddly enough, ‘stakeholders’ often feel that they have a stake in the use of a resource, but not necessarily in its stewardship. Our familiarity with our surroundings can breed disinterest or even contempt. We see the same landscape features so often that it can take a visitor or newcomer to point out to us how special these features are. And even then, we may need some convincing. Our surroundings are our ground zero -- our normal.

So, how can interpreters help strengthen this identification with locality and help visitors find something special in the normal, everyday place?

Sensitisation to, and celebration of, the normal are for me what identity-building design is all about. Here are some techniques for the practitioner to stimulate new interest in the familiar. They emerged from my work in landscape architecture and are applicable in most fields of interpretive design.

1. Distill: remove extraneous paraphernalia until the essence of the place shines forth. Our prize-winning design for the front of Schönefeld Airport in Berlin was based on a reductive approach. We pared down the fencing, paving and signage which had accumulated over the years until all that was left were the pines and the ‘beautiful field,’ after which the place is named.

2. Perspective change: set up an unfamiliar viewpoint. Get up close to the tiny things and get an overview on the big ones. This ‘high-chair’ allows a panoramic view over fields of rushes in the Elbe flood-plains. Nearby we embedded its twin, a ‘low-chair’, giving people an immersive experience among the rushes.

3. Encounters count: elicit a physical and emotional response by pitching people into a physical encounter with the phenomena. If information is 2-dimensional and being there is 3-dimensional, the full 4-dimensional experience is engaging with something in an interactive process in real time. This is learning through experience. We experience phenomena by placing ourselves in relation to the experience, not just intellectually but with our whole selves, in motion. Given a ‘situation’ and some action, enthralling facets of both ourselves and the phenomena are revealed. This labyrinth boardwalk triggers disorientation, trepidation and, in a sense, respect, which echo our archaic responses to traversing a bog.

4. Flag up: indicate the significance of the ordinary with the judicious use of signifiers. Just as putting a frame around or a pedestal under an object can elevate it to an artwork, symbols need not only be two-dimensional. This unexpected, large, red chair outside an agricultural museum catches the eye and redirects it to the quite ‘normal’-looking paddocks and orchards beyond.

5. Change the intangible to the tangible: make the intangible heritage of a place, such as historic events or people long dead, more real. These should be materially manifested in some form to make them tangible. Here the residency of Friedrich Wilhelm I in Alt Landsberg is brought to life by comical figures:

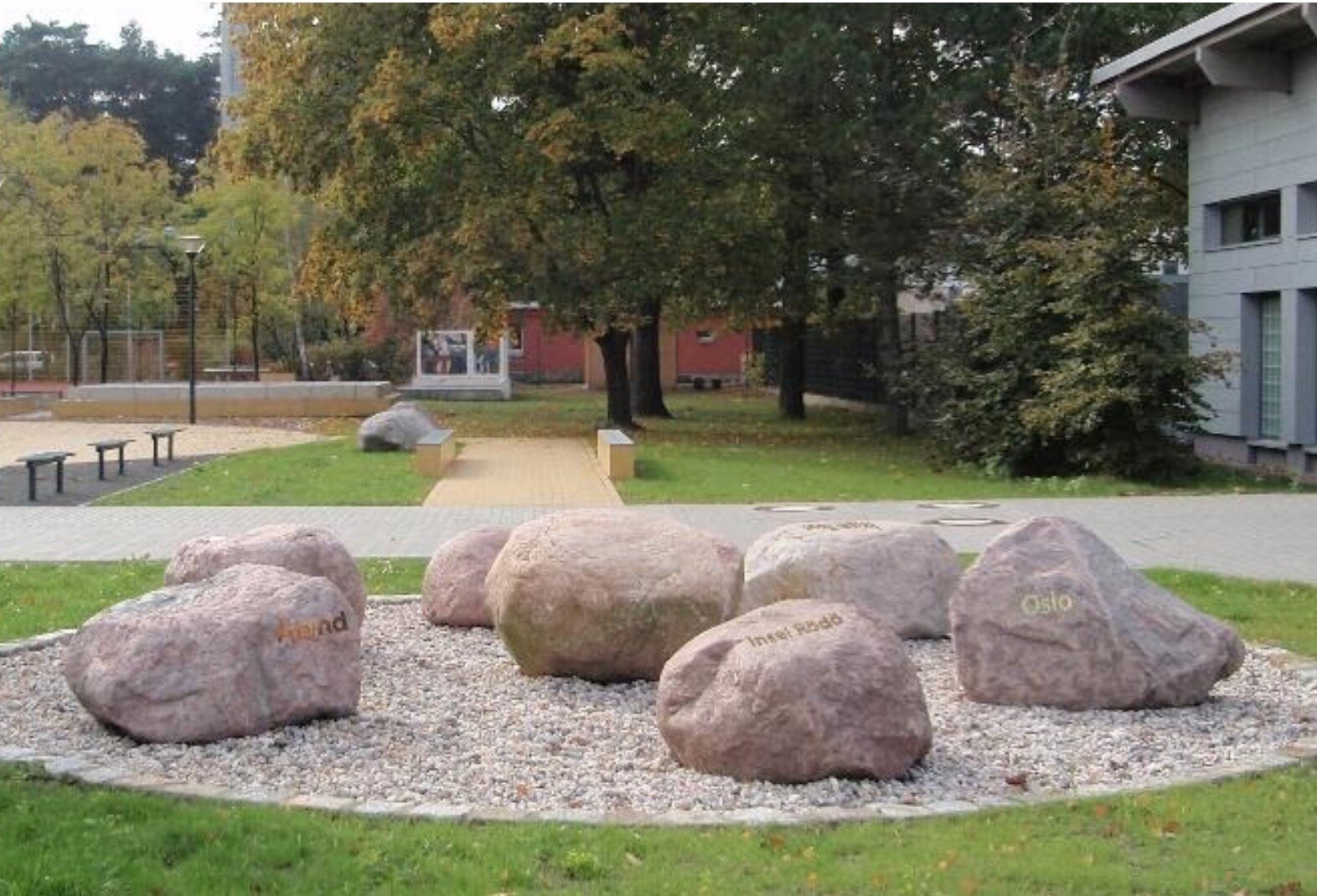

6. Relate to the whole: position the location into a larger frame of reference by revealing interesting new dimensions and significance. These stones in a school yard in Königs Wusterhausen, Germany, are tagged with the names of localities thousands of kilometers away in Norway and Sweden from which they were transported by the ice caps as little as 10.000 years ago.

7. Define, holistically: give a phenomenon physical limits, emotional context, and a name, thereby giving it more substance in our minds and enabling us to talk about it with others. The entity you present should be as holistic as possible, so essential components are not neglected by default. Our 20th Century practice of focusing on constituent parts, rather than on the whole (e.g. star-species as opposed to the ‘biome’ which includes the habitat, all the plants and animals in it and ourselves) has caused untold damage to the world. The holistic approach is thankfully beginning to establish itself in our time. The Tourist Association of Havelland, Germany, for example, ignores the haphazard county borders, and presents ‘Havelland’ as the river and its associated landscapes.

8. Mediate: direct visitors’ attention and influence their emotions in the same way as an enthusiastic guide or compere might. Good interpretive design mediates between people and phenomena. This spring bench is intended to put visitors in a whimsical state of mind for enjoying the wildflowers of the meadow.

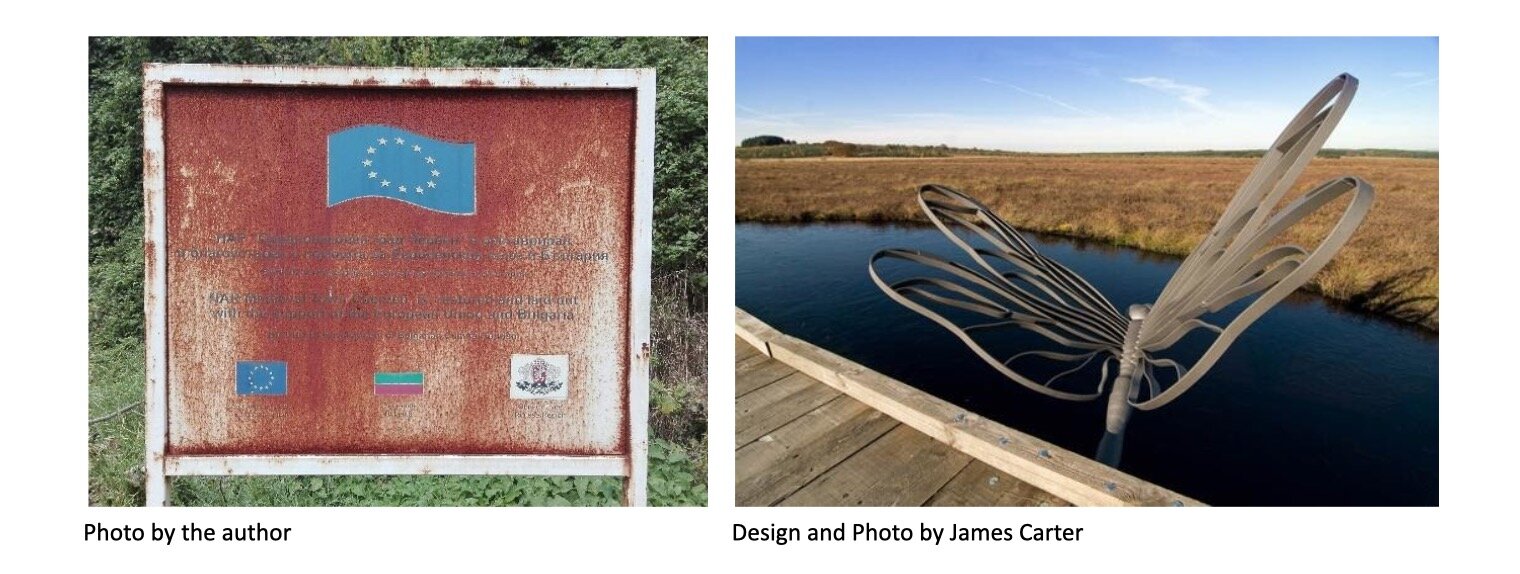

9. Value transfer: use a mind-trick often found in the world of advertising. Props with well-established value are inserted around the product of undefined merit, and the desirability of the former will ‘overflow’ onto the latter. Think of those top of the range cars and fashion models in advertisements for watches. In the same way, excellent design and the use of quality materials will signal high value for the phenomena they are attending to. This rule cuts both ways, of course: poor design and materials will signal the opposite. The neglect and poor design of the panel on the left at a historical site in Bulgaria surely devalues the site it is supposed to be promoting. Our appreciation of this dragonfly motif, on the other hand, surely rubs off on the moor beyond it with which it forms an aesthetic whole.

These are just a few of the ways in which designers can encourage the ‘normal’ to be experienced as something special. I see this task of consolidating landscape identities as essential to creating a sense of place and connection to heritage communities which can be beneficial to both people and places — to preserving our cultural and natural environments. As Meto J. Vroom put it, “identity makes identification possible.”

Angus Forbes is from the UK and has been a practicing landscape architect in Berlin, Germany for over 20 years. forbesberlin@yahoo.com