When you travel in Europe, it is extremely difficult to not visit any cathedrals or churches because they are often the most dominant structure in town and because they offer an architecturally and artistically diverse experience - even if you are not a faith-based individual. Cathedrals especially provide a constant cavalcade of stun gun WOW experiences. The buildings possess a certain magnetism that draws you in, and they elicit a sense of curiosity where you wonder - what is behind that intricately designed façade with those massive imposing doors? Each one is distinct, providing a different atmosphere and sense of reverence.

Como Church image courtesy Bill Reynolds

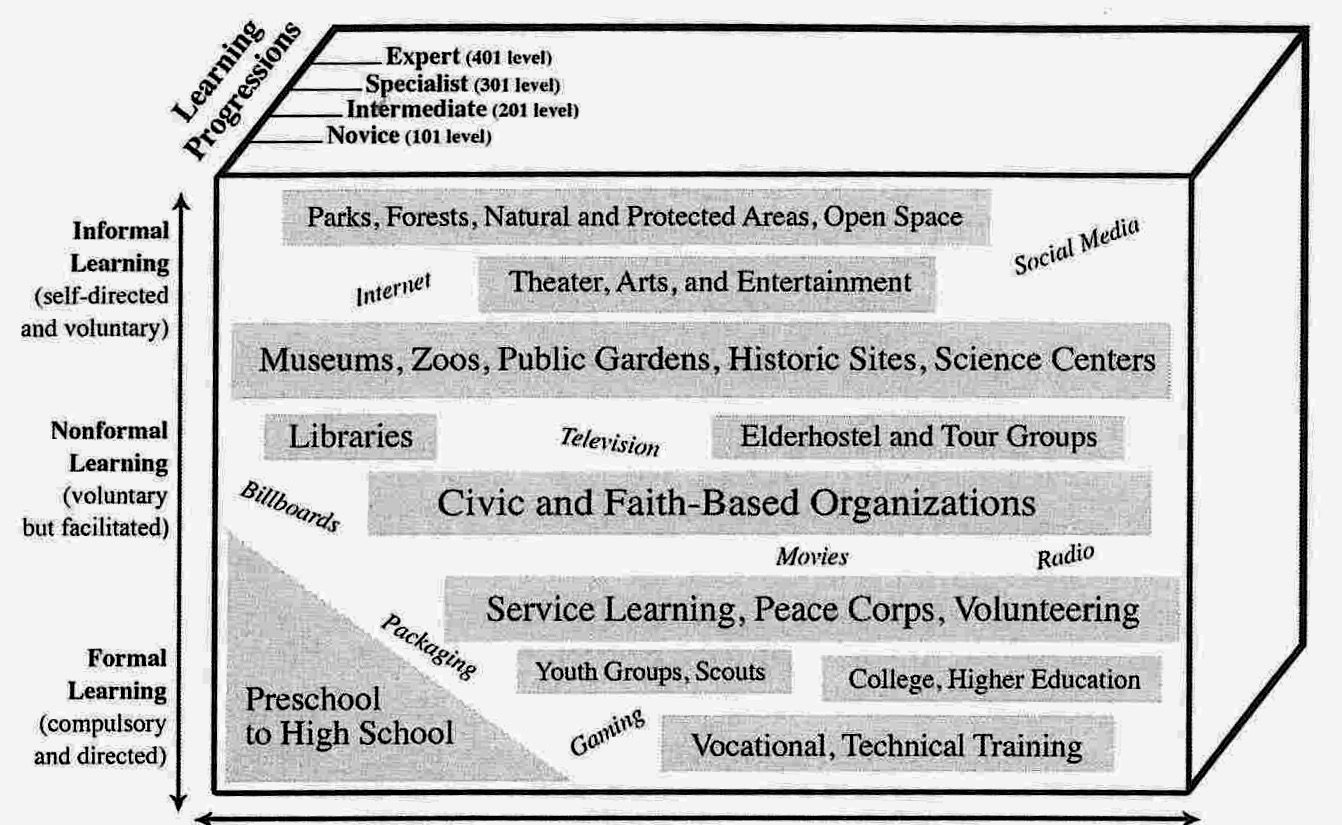

On occasion you can avail yourself of a guided group tour, but a significant visitor number choose to be on their own. These non- tour guided visitors often enter and exit after a few oohs and aahs and a few selfies.

As I watched visitors wander up one side of the pews and down the other snatching photos of what caught their fancy, I sensed a cathedral visit to a certain degree paralleled a first time visit to an outdoor park setting (a masterpiece in its own right). Both are foreign to many people’s everyday life. Some look up, a few look down, even fewer take closer looks at the amazing detail that often abounds in hidden recesses. This cursory cathedral walk - around appears somewhat aimlessly similar …

Now people HAVE been primed to expect to see beautiful objects of artistic endeavour and craftsmanship. Glimpse is often all that is being accomplished not really a seeing/absorbing experience. I found myself regretfully thinking -but each one is more than glimpse worthy- and I say this only because of my observations of the way many people visit these places of refuge and worship. (If you are not a devout catholic) many enter, gawk, snap, whisper, read various requests for small offerings, leave. What was the point? Why did the church open their doors?

Especially for all those visitors who have a non-Christian or rudimentary view, or do not have a religious background or claim a late 20th -21st century orientation towards spirituality, how do they make “sense” of the oversaturated stimuli their senses are being bombarded with? How do they relate to biblical stories and people whom the layperson has little connection with?

Como church roof interior Image courtesy Bill Reynolds

Often bewildered or overwhelmed, one doesn’t know upon entry where to go and where or how to look. Even am I welcome here? Where do we venture first and what do we focus on? Are there options depending on my interest? Helping visitors feel comfortable and approach this foreign environment with a plan, and new observational skills, without resorting to a theologian curator approach, would I wager, be very appreciated. What is the missing ingredient? Interpretive enhancement, of course!

How to prolong the glimpse and boost the level of awareness, appreciation and understanding, of this cultural masterpiece? How do we get beyond just visiting the catacombs? Interpretive enhancement, of course!

The interpreter in me is shouting help-not too loudly- we are in a church after all):

Where is the orientation? Where is the “map”?

What makes this place of worship special?

What could organize the wandering and connect the experience pieces visitors are gathering?

What could motivate a sense of exploration & discovery yet maintain reverence?

How do you help people take it all in? Do you even try?

If you live in Europe and know of any church communities who are considering improving their visitors’ experiences, let’s talk.

Como Church interior Image courtesy Bill Reynolds

Even before that practical approach we need to answer basic questions:

Who are we talking to?

What are we trying to communicate, reveal or inspire?

What do we want visitors to take away in their head and hearts-conceptual and emotional?

What kind of framework do visitors need to expand their awareness of this cultural wonder?

What are the key reference points we must supply in order to heighten appreciation for what they are seeing?

Is there a story we want the visitor to grasp and understand more fully?

Does a visit here connect our visitor to the human urge to make sense of one’s existence while trying to explain the unexplainable?

Could the use of self-guided approaches provide a helpful function?

Como church detail Image courtesy Bill Reynolds

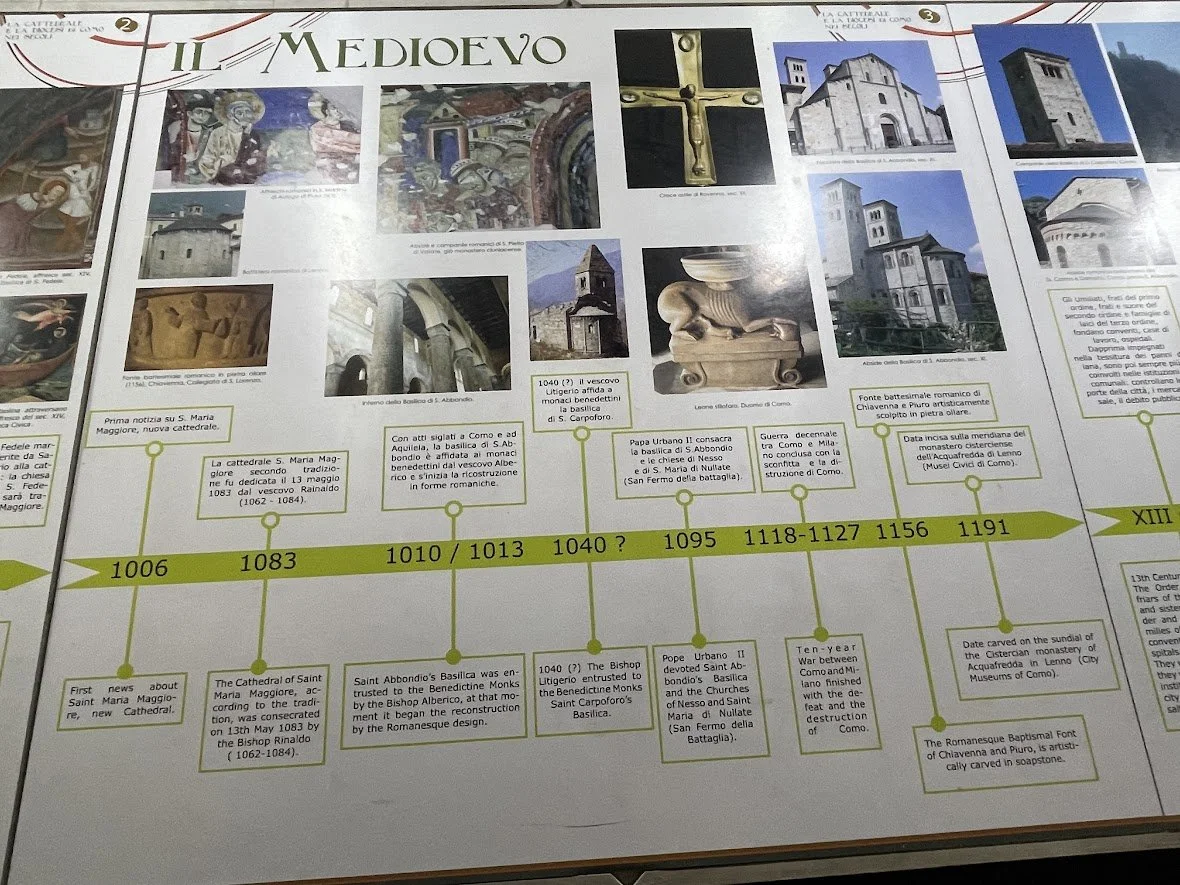

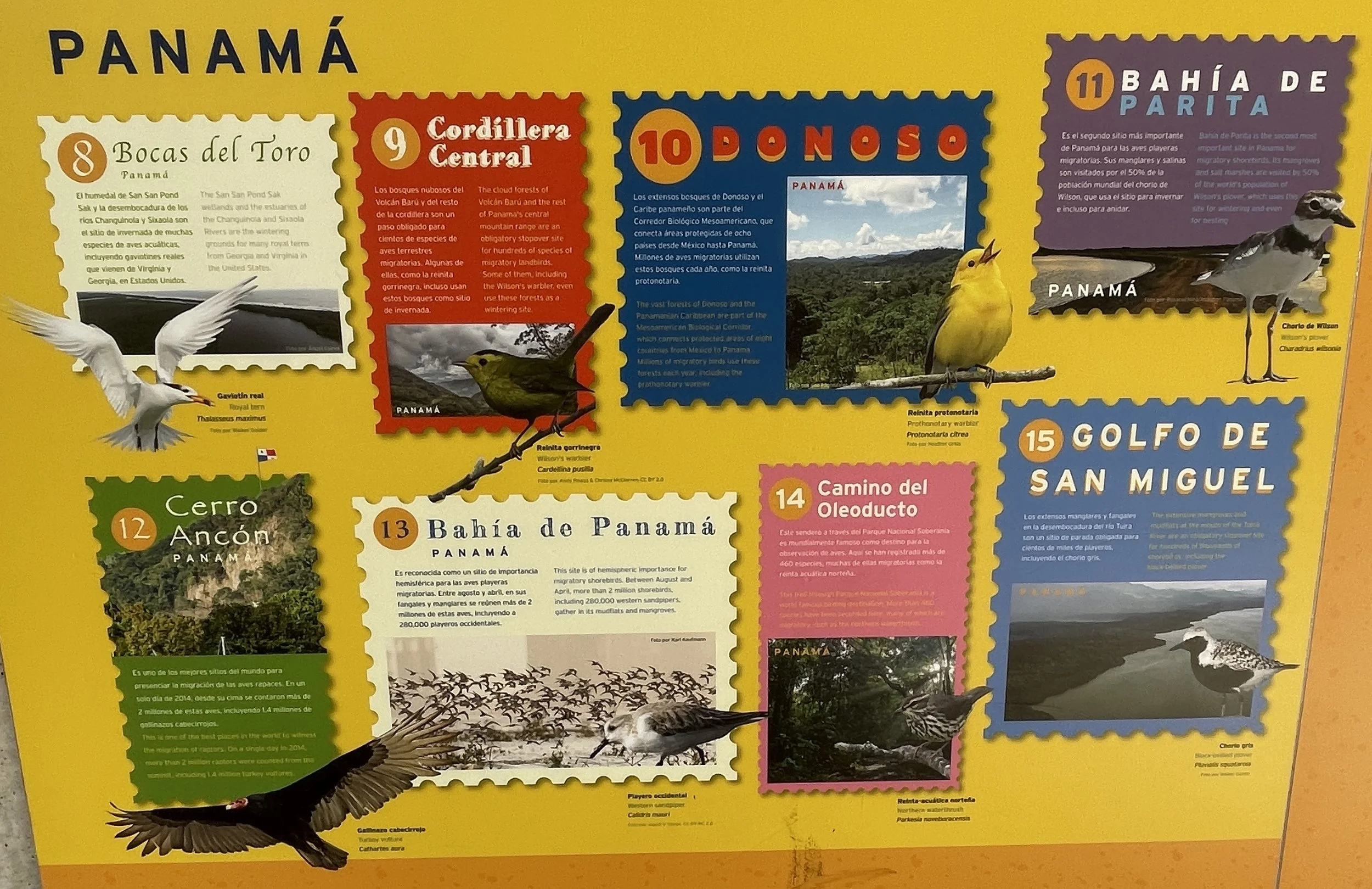

Let’s explore one self-guided approach in the famous town of Como, Italy that swarms with tourists most of the year and churches are billed as attractions that visitors are encouraged to see. In the main Como cathedral were a series of 4 long, well-lit, well- illustrated, back- to - back panels, situated so the potential reader would walk along and around them. I was only able to photograph one front side in the image below, but it had a back side and there were 3 others. They were situated near the visitor entry point inside the cathedral and distributed about.

Overview of Como cathedral timeline: Each panel on their own had a good balance of text and graphic but by lining them up, side by side, they created a challenging reading environment. The judicious use of “white space” could have been employed better to eliminate the sense of busyness & clutter on the panel for easier comprehension.

Too much, too concentrated- all in one space with no break.

Getting people to read for any length of time standing up is always a challenge. When faced with a voluminous amount of potential information, interpretive choices are paramount and the partitioning/spacing of the MOST significant points is so important.

This specific timeline dealt with the history and details of many regional buildings in addition to the actual church people were standing in. If the content is NOT directly related to what they can see in front of them -in their immediate presence- the interest and holding power is vastly diminished.

Many items referred to beautification and canonization events of interest to the clergy primarily.

Como church timeline(partial) Image courtesy Bill Reynolds

The extensive “real estate” being offered here (there were 5 more) is not the best use of this space for a church with so much to offer itself in the here and now that visitors could be encouraged to engage with. A very condensed version could have been helpful to deliver certain select messages and could have provided a welcoming context for one’s visit.

Timelines have a place but they should tie in to a very clear purpose. I invite you to read our December post titled Comparative Timeline: A Lost Art for further discussion about the interpretive power potential of timelines.

Let’s dig in to review a select few timeline examples:

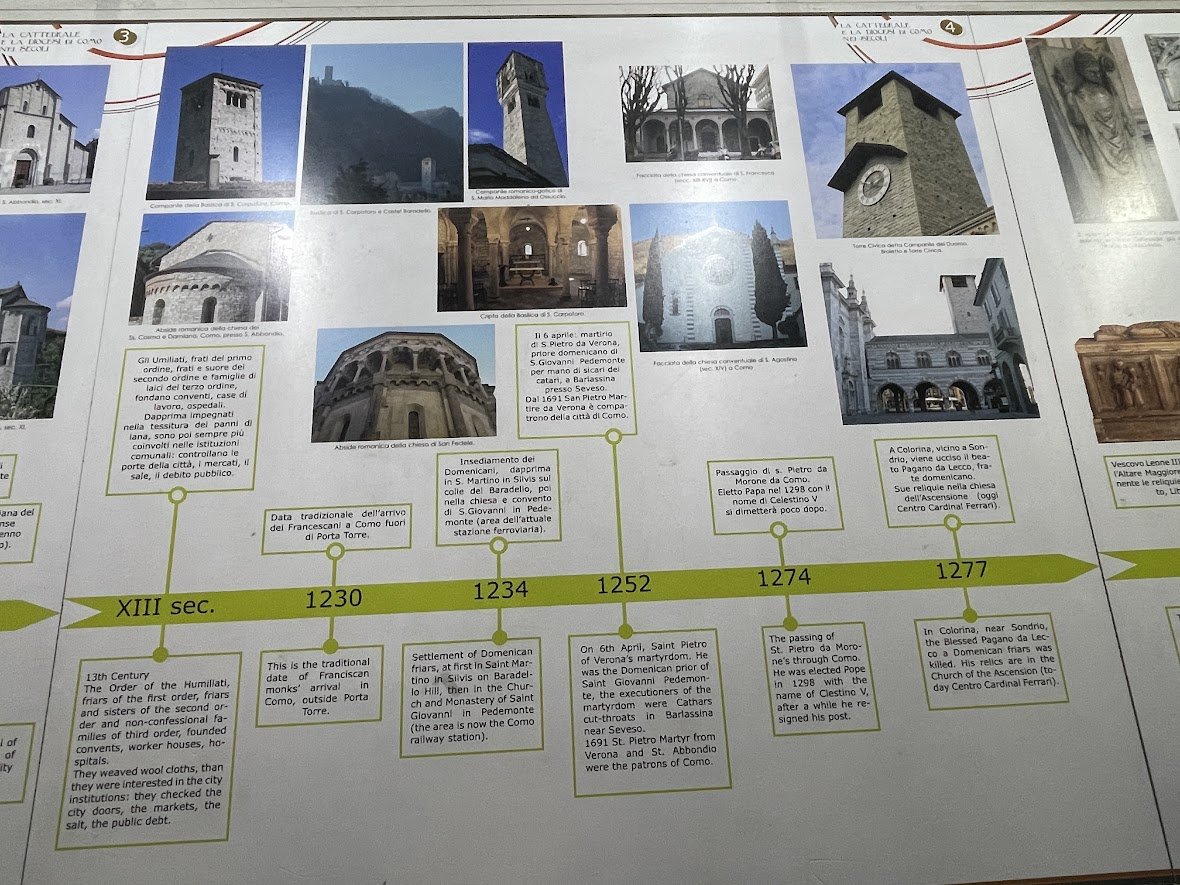

· 1191 text “Date carved on the sundial of the Cistercian Monastery of Aquafredda in Lenno (City Museums of Como)”

Como church timeline first close-up

Interpretive Observation: The images chosen above the timeline do not connect to the text about a sundial. Images should connect easily and reinforce what the chosen text refers to. They should pair well otherwise choose a different text if possible, or don’t include an image. There is a reference to a museum in brackets. Should the reader assume that is where one needs to go to see this item? This needs to be clearer and can be a good technique to encourage visits to other interpretive sites.

Como church timeline 2nd close-up Image courtesy Bill Reynolds

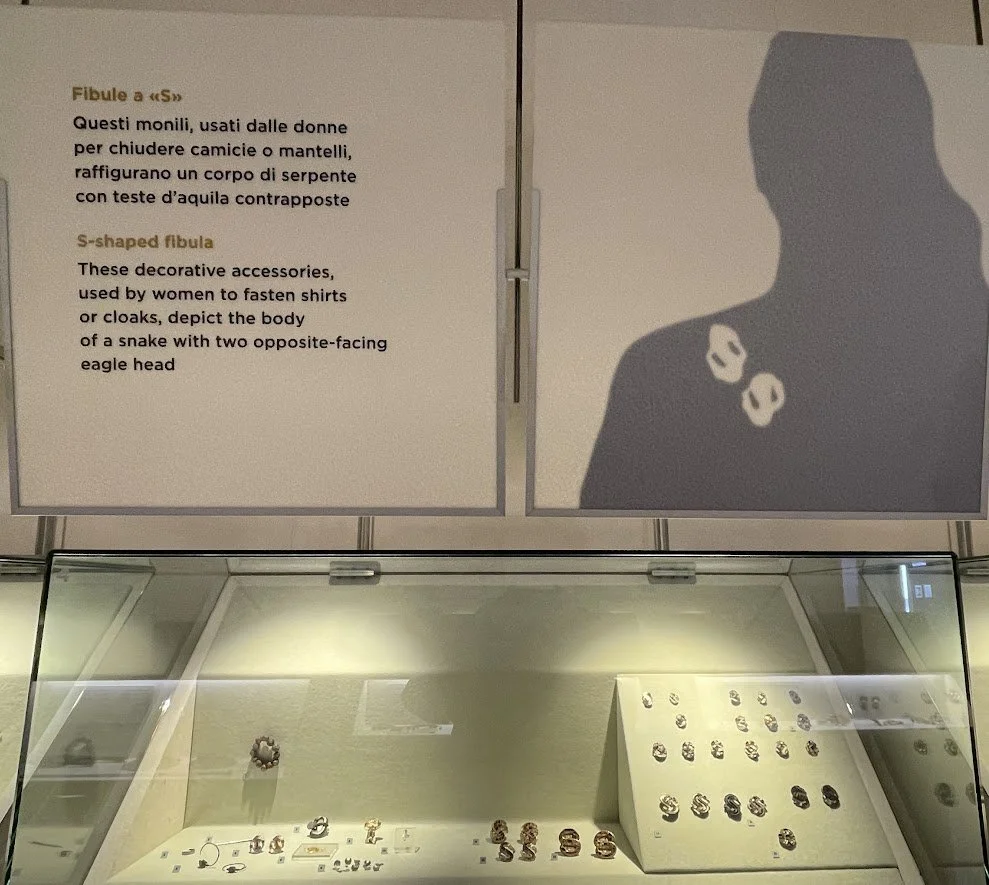

· 1274 text “The passing of St. Pietro de Moronne through Como. He was elected Pope in 1298 with the name of Clestino V, after a while he resigned his post.”

Interpretive Observation: Who was this written for? Certainly not the general visitor. Perhaps this display was created for a different audience and was repurposed and placed here. In any case, again the image chosen above this text seems to have no relation to the Saint who is the focus of the message that was chosen for us to read. As interpreters, we need to consider our reader and assess all of the possible things to say about our subject then choose the most important item(s) that are relevant to the overall purpose of the communication.

Interpretive sites have a tendency to choose dates and names as what we think our readers would be most interested in (caution). It appears that the writer figured that the next most important detail about Clestino V was that “after awhile he resigned his post.” Either this item should have been left off or if this was significant, the reader needed a little bit more about the why, even if the intent was to have a dangling mystery of intrigue. Adding a source to find out more (in brackets) would have been an option, as was employed with the sundial.

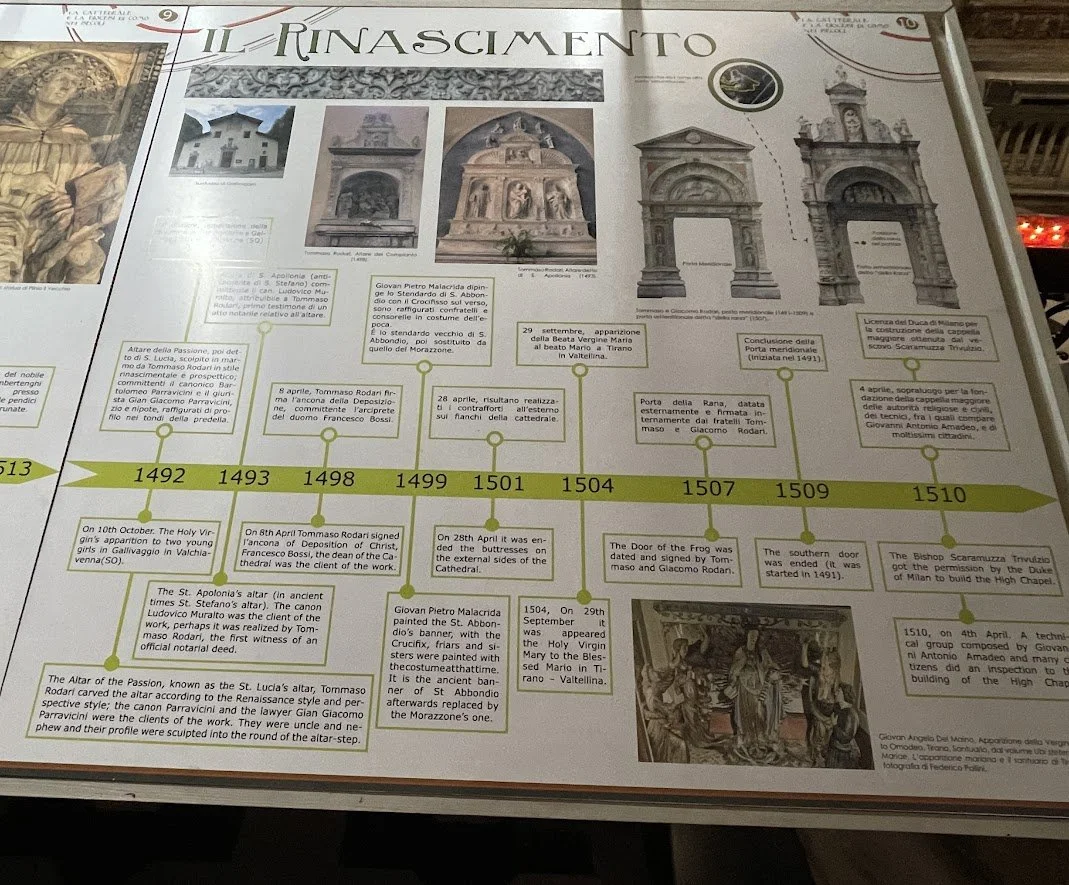

Como Church timeline 3rd and fourth close-up

· 1492 text “Tommaso Rodari carved the Altar of the Passion according to the Renaissance style and the perspective style; the canon Parravicini and the lawyer Gian Parravicini were the clients of the work. They were uncle and nephew and their profiles were carved into the round of the altar step.”

Interpretive observation: Signage should inspire people to DO something. Style must be important because that was chosen to be highlighted in the text. Do we want visitors to be looking for characteristic elements of the Renaissance style and a perspective style? How would we help them to know what to be on the lookout for?

The custom of incorporating patrons into artwork was “a thing” during certain periods, so we are alerted to this yet there does not appear to be an image in the timeline with a small sidebar circle illustrating these profiles, as was done in the next example.

· 1507 text “The door of the Frog was dated and signed by Tommasa and Giacoma Ridari. “

Interpretive observation: This time the image shows the door being talked about (more like a gate-a translation issue). In addition, there is a wonderful close-up of the sculpted frog in a little circle up and to the left. However, without context the visitor has a difficult time figuring out why this is such a significant item in the history of the Como church. If this is a contemporary feature then wonderful, but we need to indicate this and where? This last weakness reinforces the key point of dealing with what the visitor can see right now as crucial to gathering and maintaining their interest.

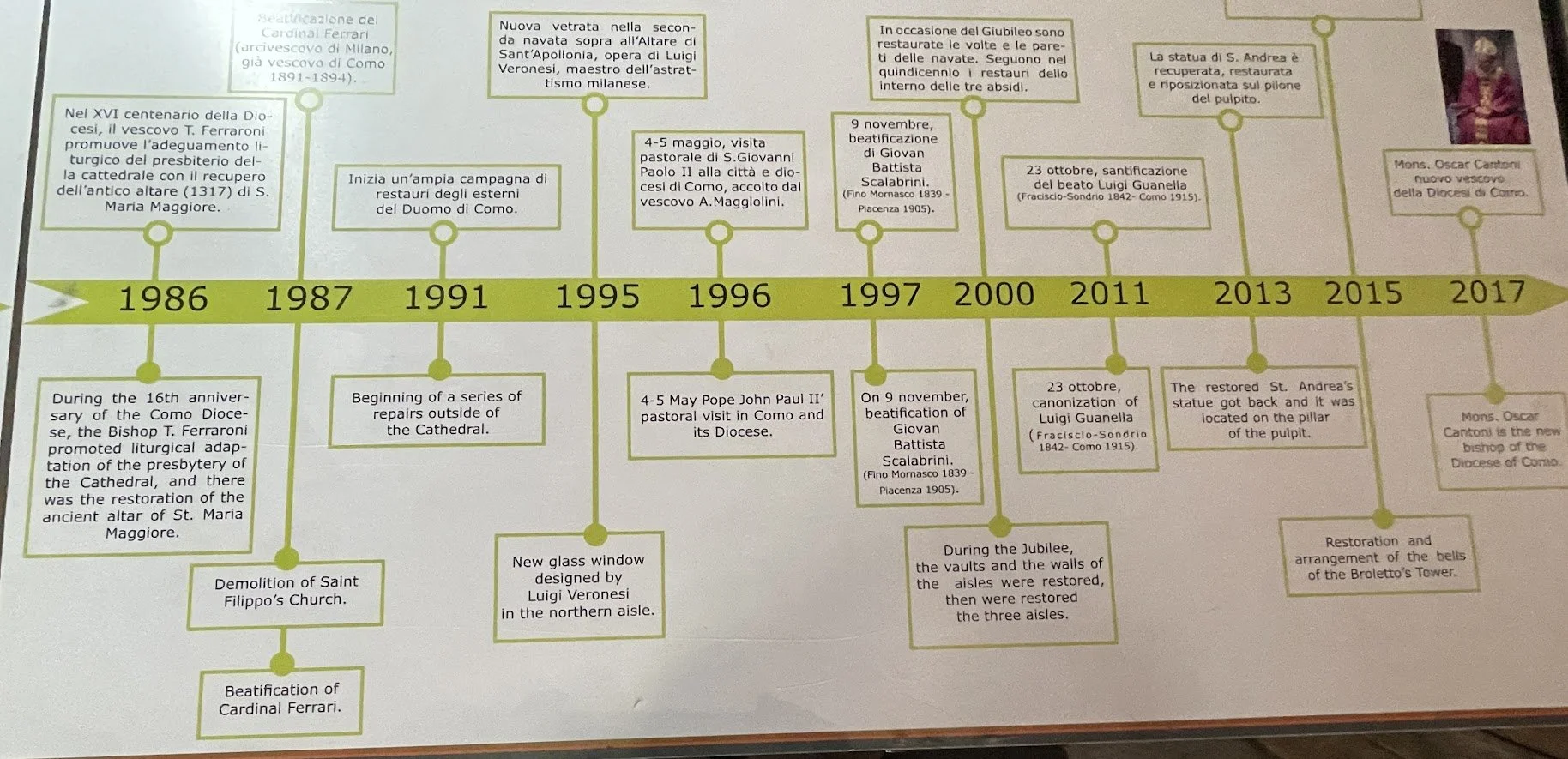

Como church timeline 5th close-up

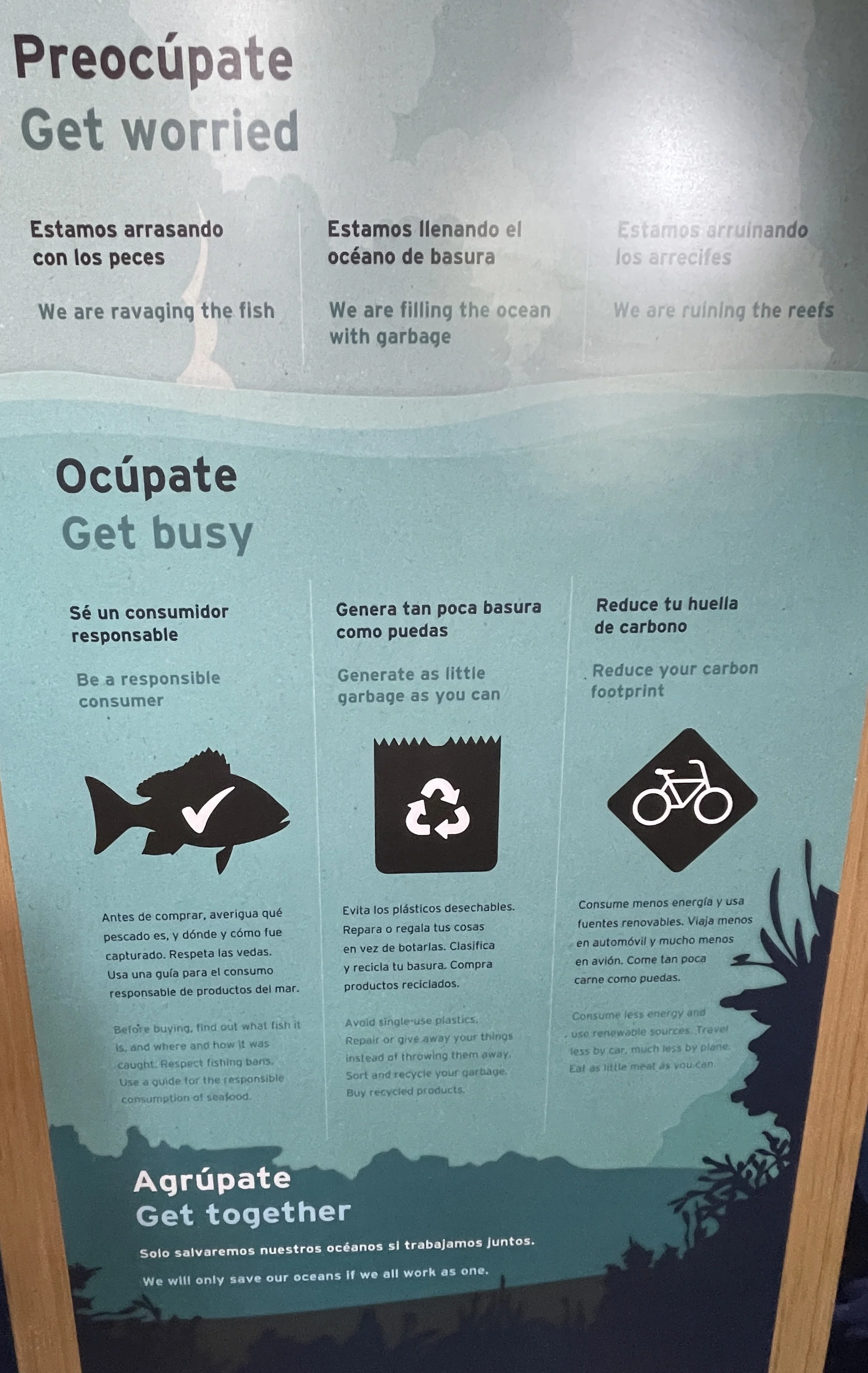

I was struck by many of the contemporary dates as they covered important restoration items which even with a visitor cursory timeline review, this would impress upon the reader that restoration was ongoing and important to the church. This I posit, could be a key message worth highlighting that could relate to an ongoing need of funding.

Opportunities to leave money behind for the upkeep of these incredible monuments of human creative ability needs a much higher profile. How often are we as visitors reminded that these artistic wonders need refurbishment and require resources to do that? Where does the money come from to maintain these cultural treasures? Where does the money come from to provide a more enlightened on- your - own visit?

When are you ever asked – did you feel better as a result of your visit today- did the level of artistic creativity and endurance speak to you today? What was that series of moments worth that took your breathe away?

Be Aware: Time periods, and the names of architects, clergymen, artists, sculptors and woodworking craftsman, become the centrepiece of what has been chosen to be told. Think of your audience. Facts and figures, names and numbers abound, similar to what used to be the bread and butter of museology and historic sites. References are made to biblical stories and people whom the layperson has little connection to.

A future post will highlight some examples of focused interpretive signage being utilized in the interior of churches.

Bottom line folks: If we want visitors to take notice, read and remember. Simplify, Simplify, Simplify. Choose, Choose, Choose.